Noto Suoneto

Noto Suoneto

Birgitta Riani

Birgitta Riani

The Diplomat – September 22, 2020

Earlier this month, Japan’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) selected Suga Yoshihide to replace the outgoing Prime Minister Abe Shinzo, following his resignation due to ill health. With Abe’s sudden exit in the throes of a global pandemic, the appointment of Suga, who took office on September 17 after serving as Abe’s chief cabinet secretary throughout his second term, is the LDP’s means of ensuring a degree of continuity on Abe’s major policy initiatives. Suga has himself made this bias for stability explicit, vowing to maintain the tenets of “Abenomics” in economic policy, and continue the country’s coronavirus measures.

While his appointment to the premiership can be seen as the safest choice domestically, many observers have expressed apprehension over his lack of experience in the international arena. Throughout his career, Suga has mainly been involved in crafting domestic policies. On foreign relations, he has again emphasized the importance of continuity, as can be seen through his promise to maintain strong ties with Asian nations, strengthen the foundation of the Japan-U.S. alliance and stand up to China when necessary. At the same time, he has promised to take his own diplomatic approach, while at the same time acknowledging Abe’s foreign policy achievements and the difficulty of filling his predecessor’s shoes.

The Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy (FOIP) is undoubtedly Abe’s flagship foreign policy initiative. Premised on a delicate combination of balancing against China’s rise and hedging against the decline of Pax Americana, the FOIP has led to the intensification of Japan’s strategic relations with key regional powers, including India and Vietnam. Among the most important is Indonesia.

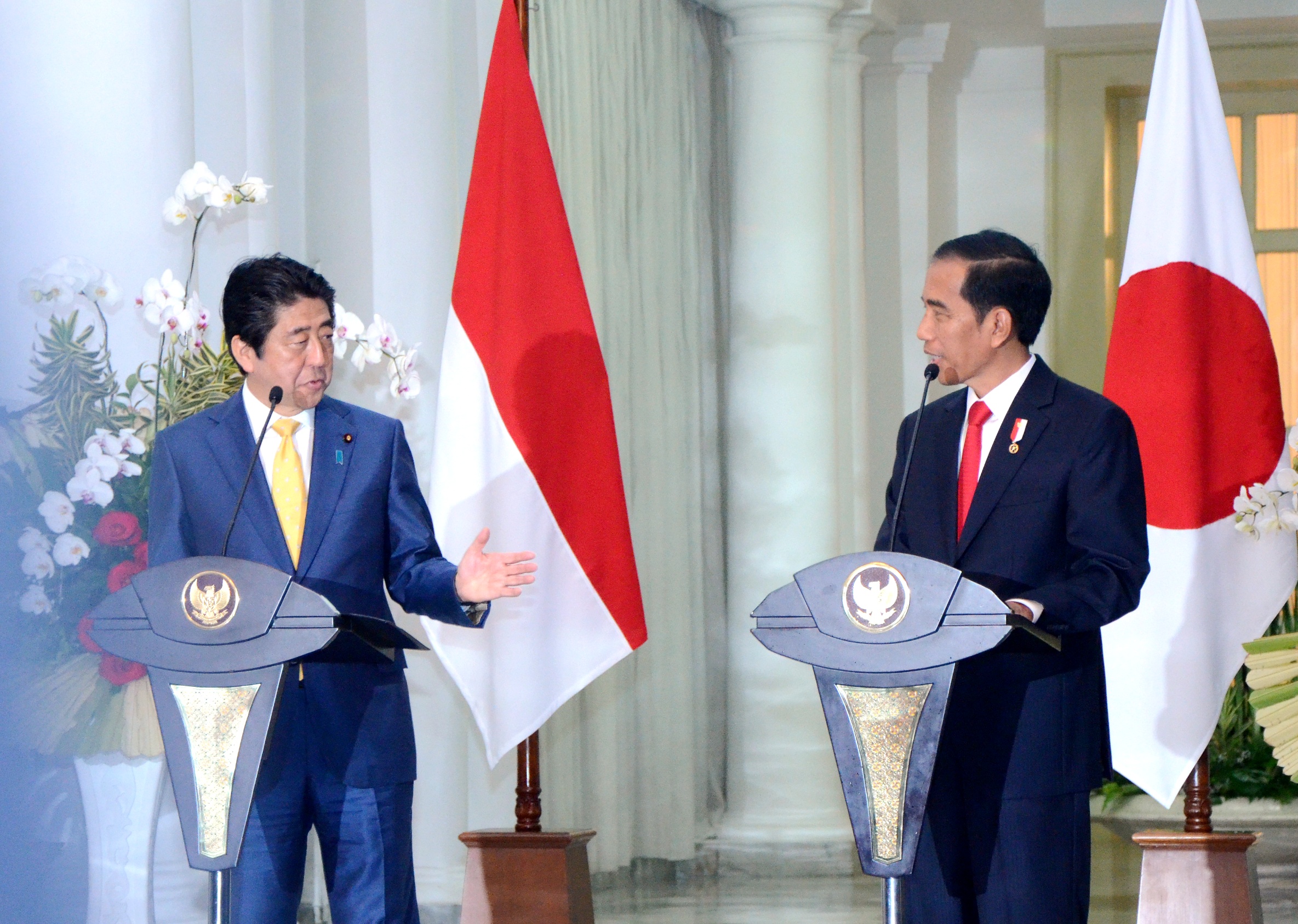

The Abe years saw a considerable deepening of Japan’s relations with Southeast Asia’s most populous nation. On the economic front, Indonesia has welcomed Japanese investment with open arms. Japan was the country’s second-largest source of FDI in the first half of 2019. Japan has also supported President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s ambitious infrastructure agenda.

On questions of defense, Abe and Jokowi saw eye to eye on the importance of maritime security and in 2016 announced the establishment of the Japan-Indonesia Maritime Forum to drive forward cooperation on this front. The two nations have also cooperated closely since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. In July, Japan extended the Indonesian government a loan of 50 billion yen (around $478 million), as well as a grant of 2 billion, in order to support its fight against the coronavirus. This has come on top of other forms of COVID-19-related aid.

Under Abe, Japan has attempted to moderate the growing competition between the U.S. and China in the region. Here, too, Indonesia is important. While rising superpower tensions pose a host of risks to the relationship between Tokyo and Jakarta, Suga fortunately comes to the job with a good deal of accrued trust.

In the context of China’s increasing power and assertiveness, Indonesia is in a position to offer Japan strategic opportunities. For instance, following China’s assertive coast guard activities around the Natuna Islands early this year, Indonesia asked Japan to invest in islands adjacent to disputed waters in the South China Sea. Moreover, the Indonesian government has recently expressed its desire for a Japanese company to join the consortium constructing the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway, some five years after it chose a Chinese firm for the project. These recent interactions leave little doubt that Indonesia “uses” its engagement with Japan to demonstrate its disapproval of China.

As part of his COVID-19 economic recovery efforts, President Jokowi has instructed his government to seize any opportunities that arise from Japanese corporate migrations out of China as the pandemic wanes. Indonesia also issued the first Samurai Bond in Japan’s financial market this year, receiving positive responses from Japanese investors. Given the region’s current condition, Suga has a golden opportunity for Japan to maintain and deepen trust with Indonesia. But he has to prove his ability to not only maintain what Abe has built but also exploit the untapped potential in the Indonesia relationship.

Like Japan, Indonesia has had its reservations in associating too closely with either of the two superpowers. Indonesia’s key role in developing the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific (AOIP) testifies to Indonesia and Japan’s shared perspective on the region as an interconnected strategic unit. At a time when deepening relations with China or the U.S. is complicated by their accelerating rivalry, Indonesia and Japan should instead work together to strengthen longstanding ties.

In line with the LDP’s overall message of continuity, the new Suga cabinet has kept critical Abe appointees in place. Taro Aso, Kajiyama Hiroshi and Motegi Toshimitsu retained their posts as the ministers of finance, trade and industry, and foreign affairs, respectively. All three have played important roles in pushing forward cooperation between Japan and Indonesia. In December 2019, Taro signed an MoU to establish a local currency framework for bilateral trade and direct investment with Indonesia’s central bank.

In July 2020, Kajiyama held a virtual meeting with Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan, Indonesia’s Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs and Investment, and Minister of Industry Agus Gumiwang. During the meeting, the two sides discussed the relocation and expansion of Japanese companies and investments to the new Batang Industrial Complex in central Java, and Indonesia’s bid to become a regional export-hub for automotive products. When Motegi visited Indonesia before the pandemic, the two governments confirmed their commitment to strengthen bilateral partnerships in fields such as infrastructure, human resource development and maritime cooperation, as well as synergizing the FOIP strategy and the AOIP at the regional level.

Like Suga, these three ministers can be expected to continue policies from the Abe era. In late August 2020, Motegi paid a visit to several Asian countries to resume diplomatic exchanges that had stalled due to COVID-19. A state visit to Jakarta or another form of high-level dialogue would help get relations between the new Suga administration and Jokowi’s cabinet off on the right foot.

Prime Minister Suga’s early diplomatic moves will play a crucial role in determining the trajectory of Japan’s relationships beyond next year’s election. While it is expected that he will initially look inwards, Japan’s new leader must not forget to reach outwards and renew the trust of Japan’s long-established strategic partners.

The reality is that Indonesia and Japan are in many ways natural friends. As maritime democracies which are soon likely to become the world’s fourth and fifth-largest economies, the two nations have much to gain from adopting a common political, economic and social vision. Stronger bilateral cooperation between Tokyo and Jakarta would counteract to a certain extent the political instability and economic turbulence that have increasingly come to dominate the Indo-Pacific region.

Noto Suoneto is a foreign policy researcher affiliated with the Foreign Policy Community of Indonesia (FPCI) Jakarta with research interest on East Asian affairs and the international political economy.

Birgitta Riani, a graduate of Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University, Japan, is a researcher at the FPCI with interest in the geopolitical dynamics of the East and Southeast Asia.