Camille Bismonte

Camille Bismonte

Kareeda Kabir

Kareeda Kabir

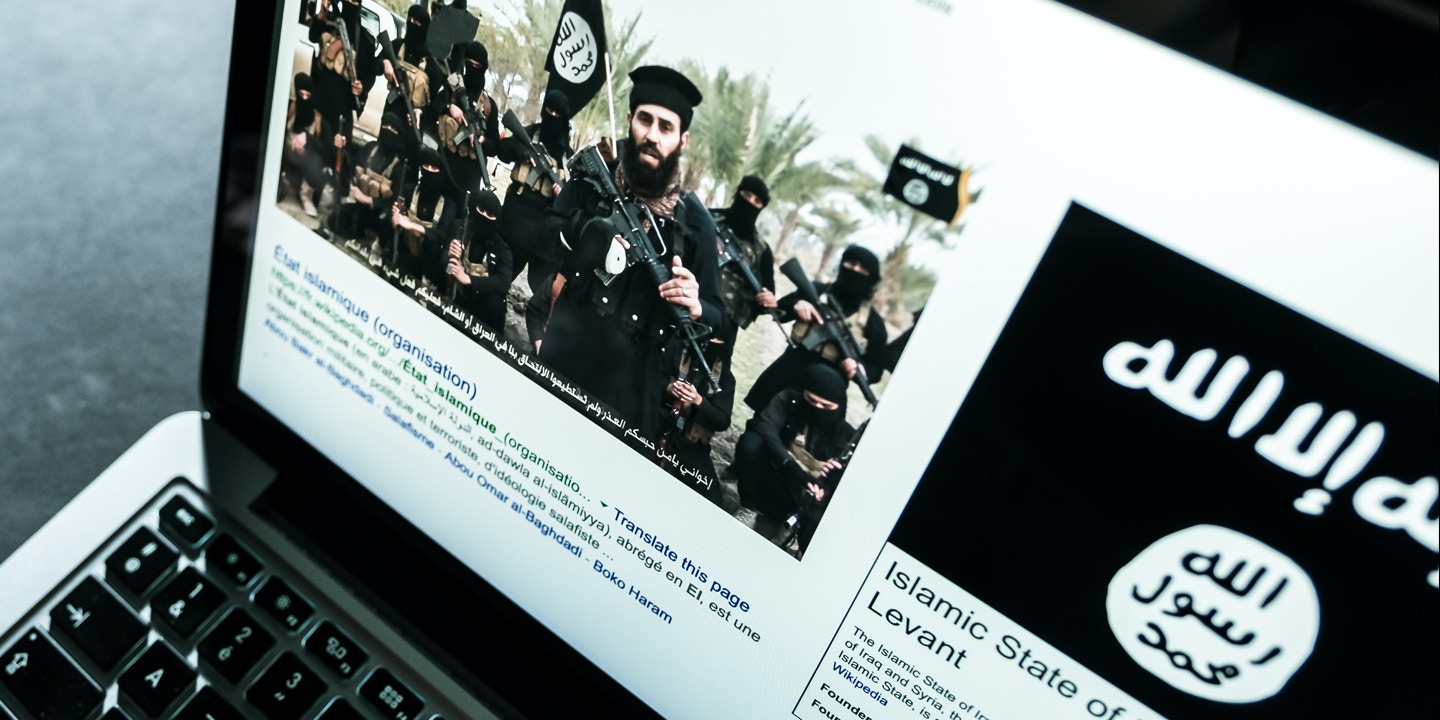

Amid the pandemic, it has been said that Indonesia has found itself fighting two viruses. The first being the coronavirus pandemic, and the second being the “virus” of religious radicalization. The lethal combination of an ailing global economy combined with the strain on healthcare systems has pushed people to find other outlets to obtain the resources and support they need. Unfortunately, one outlet in Indonesia and the Philippines appears to be militant Islamic online radicalization through increased internet saturation, fueled by a need for a sense of community amidst the calls for self-isolation during the pandemic.

The impact of these two viruses simultaneously can be shown to be particularly impactful to Indonesia and the Philippines, which are the two countries in ASEAN most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic with over 160,000 cases in Indonesia and over 200,000 in the Philippines as of August 26, according to Johns Hopkins University’s Coronavirus Research Center.

Online radicalization is nothing new. It began with the onset of the internet, on forums created by white supremacist groups as early as the 1980s to recruit and share information and resources across the country. This strategy has now been replicated by almost every cult, bad actor, radical group, and terrorist organization.

In the Philippines, a country with a significant Muslim minority, radicalization crops up in rural areas in the Muslim south. It is a by-product of the Christian-led government of the Philippines and substantial Christian migration from the north. Indonesia is a Muslim-majority country, and while generally a more moderate strain of the Muslim religion, there is increasing growth of Islamic fundamentalists in government and society.

ISIS internet forums have interpreted the pandemic as a form of retribution for the treatment of Muslim Uighurs in China. Nevertheless, therein remains calls for taking advantage of the vulnerabilities of governments during this time. According to Dr. Joshua A. Geltzer, Executive Director of Georgetown University’s Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection, and former Senior Director for Counterterrorism for the White House, in a Virtual Roundtable Discussion for the Foreign Policy Community of Indonesia (FPCI), “COVID-19 has accelerated the concern because of the extent to which people are, by design, retreating [and] spending more time consuming propaganda recruitment materials and conspiracies that are deliberately perpetuated by groups seeking to recruit and radicalize.”

The sense of isolation as the breeding ground of Islamic radicalization has been brought to the forefront in the diasporic communities of Indonesians and Filipinos in East Asia, where there have been instances of radicalized domestic workers in Hong Kong or Singapore. This issue has been shared by Dr. Noor Huda Ismail, the Founder of the Institute for International Peace Building in Indonesia, who believes that the lethal combination of a captive, isolated audience and a radical narrative makes those who feel isolated particularly susceptible. Pro-Daesh groups in Indonesia and the Philippines have come to rely on social media such as Telegram and Facebook for propaganda and fundraising to support their terrorism efforts under the guise of aid during the ongoing COVID-19 crisis.

Indonesia is host to one of the highest number of internet users globally. As of June 2019, 171.26 million out of the country’s 260 million were active internet users. With the additional instability of the pandemic in countries such as the Philippines and Indonesia, many have turned to the internet for camaraderie during these trying times. This is attributed to a lack of governmental support in their financial institutions and healthcare systems.

With a sense of isolation, there have been additional stressors, such as economic instability. Before the pandemic, the International Labour Organization noted Indonesia’s 15-24-year-old unemployment rate (17.04%) as the second-highest in Southeast Asia, and this number is expected to rise. Moreover, Indonesia’s Central Agency on Statistics (BPS) confirmed on August 5 that Indonesia’s economy had contracted for the first time in twenty years, which puts the nation at serious risk of a COVID-19 induced recession.

With a record high unemployment of 17.7%, the Philippines is expected to plunge into a recession with an anticipated 9.4% contraction. With their country’s financial and healthcare systems suffering, many have felt the repercussions of the pandemic’s financial strains. Hence, they may be more susceptible to finding solidarity in their suffering online, or at least a panacea for their financial woes.

The allure of jihadist groups to women has been particularly amplified, as people become more susceptible to radicalization in their search for a sense of community. In this way, the issue of what causes radicalization is not simply a question of ideology but of how being a part of this community online can grant a sense of purpose. Moreover, there have been additional concerns of jihadist media being used as a vehicular medium for encouraging women to become radicalized, allowing them the sentiment of self-autonomy when they may feel traditionally powerless.

This change in ISIS’ attitudes towards women has been ongoing since 2015 since ISIS believes that women are less likely to be targeted as terrorists and are especially active online as recruiters on jihadist forums. Additionally, women have been radicalized through e-dating ISIS fighters, with promises of a better life.

In a report written by IPAC analyst Nava Nuraniyah on The Evolution of Online Violent Extremism in Indonesia and the Philippines, women’s roles in extremist media have become much more visible. Although women have traditionally been barred from accessing extremist public spaces or taking an active part as combatants, they are empowered through social media to play more active roles as propagandists, recruiters, financiers, or even suicide bombers.

The rise of suicide terrorism during the pandemic is one of the predominant issues raised by Dr. Rommel C. Banlaoi, Chairman of the Philippines Institute for Peace, Violence & Terrorism Research. In discussing the Marawi Siege of 2017, a five-month battle between ISIS-affiliates and the Philippine Army. He noted that even after the bloody urban warfare during the Marawi Siege, the Philippines had witnessed at least five major suicide bombing attacks, and one failed suicide bombing attack.

In Indonesia, out of the ten suicide bombings that have taken place since 2014, three women were amongst the suicide bombers arrested, according to Dr. Zachary Abuza, a professor at the National War College in Washington, DC. Additionally, the Surabaya Bombings of 2018 also serves as a grave reminder of whole families of suicide bombers indoctrinated into the pro-Daesh cause.

This is prevalent “as Jihadist groups are taking advantage of these economic difficulties to recruit more fighters, not only through ideological recruitment but also through material inducements promising them money if they want to fight in the name of Allah,” according to Dr. Banlaoi. He also fears the pandemic is also significantly hampering law enforcement authorities’ ability to respond to terrorist threats.

The Brookings Institution analyzed a number of themes that occur in combatting violent extremism. Though these were developed through an analysis of developing countries, the threat of COVID-19 has created circumstances where these themes can be seen everywhere. First, as schools and extracurricular activities have shut down entirely or moved online, more time is spent online to either make up for it or to continue it to some degree. This leaves people, especially young people, susceptible to radicalization. Next, the pandemic and more access to the Internet allows for COVID-related misinformation related to racial, ethnic, religious, etc. groups to form and spread.

In the U.S., for example, right-wing groups have capitalized on COVID-19 to link the virus to religious or ethnic minorities. In other places, this type of rhetoric can be seen with refugees, for example. Another example is community policing going down, which lessens the chances of someone catching another person’s signs of radicalization. In the U.S., almost a quarter of jihadists are reported by a family or community member, almost 10% are reported from the general public, and almost half are monitored by an informant. This type of reporting can be hastened when schools, extracurriculars, and other community gatherings are canceled or shut down. Lastly, generally speaking, with unemployment up, radicalization is more likely. All of these factors are present due to COVID-19 lockdowns or rearrangements, and we must, therefore, keep online radicalization in our priorities as we deal with the virus.

The COVID-19 pandemic fight is often couched in terms of addressing the physical, health, and economic risks that people have been facing. What must not be forgotten is that this pandemic, and the physical and emotional isolation utilized to fight it, also creates fertile grounds for an enhanced risk of substantial jihadist terrorism due to vulnerable populations in light of the pandemic.

Camille Bismonte is an associate researcher at the Foreign Policy Community of Indonesia (FPCI) in Jakarta, Indonesia and a senior at Georgetown University.

Kareeda Kabir is a linguist and a recent graduate of Georgetown University. She researches violent extremism and violent misogyny.